Competency is an essential determinant in whether a task or activity is completed successfully and efficiently, and can be defined as a combination of skills, job attitude and knowledge that is reflected in behaviour that can be observed, measured, and evaluated.

The author is encouraged that historical ranking (‘next in line’) and/or time-serving (’length of service’) led prerequisites in appointing practitioners to key/senior technical positions or identifying practitioners to enter a development pathway are increasingly becoming superseded by more sophisticated, competency-based requirements inspired by the positive experiences of learning professionals. This evolution in thinking has also led to greater clarity, objectivity and equity.

This does not mean unnecessary complexity, as the learning profession has identified a number of useful models in existence that can be adopted in setting out and assessing the competency required of prospective and existing practitioners.

These range from a more basic coverage of:

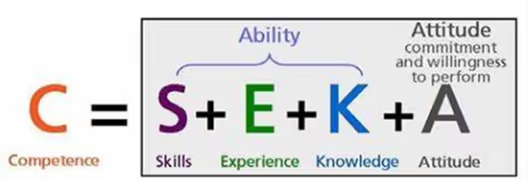

To the author’s favoured SEKA Model as shown:

The SEKA Model shows that competence should be seen as a sum of a number of attributes (listed and defined here in alphabetical order):

Attitude is highly significant in influencing performance and is widely held as the most important factor in learning, to build upon the potential provided by knowledge and skills. Unfortunately, attitude is one of the more difficult attributes to accurately and reliably assess!

The SEKA Model has been adopted very successfully as a framework to then set out the specific competencies required by road safety or traffic engineering practitioners in a role or through a career path, e.g. job applications; or to qualify to fulfil a specific task, e.g. road safety auditor or road safety audit team leader.

The standard Australian Qualifications Framework (AQF) approach promotes the development of predefined Units of Competency, which are then further categorised into Elements of Competency, and the requisite skills, experience, knowledge, and attitude matched and then assessed against. Units and Elements of Competency can range those deemed ‘essential’ or ‘core’ (i.e. a defining capability or advantage that distinguishes that person or role) to ‘secondary’, ‘tertiary’ and ‘other’.

The assessment process is detailed to ensure both consistency and objectivity, and nearly always involves the preparation of a formal submission (sometimes called a portfolio of evidence) by the applicant seeking the position or role. A degree of self-assessment will typically be required as a pre-requisite, before moving to a peer consideration as to whether the applicant has satisfied competency against the Units and Elements within that framework.

A range of assessment methods/tasks is typically specified, including, for example; face-to-face interviews using a standard set of questions; consideration of testimonials and references; provision of past project reports, a work journal and/or professional CV/resume tailored to the pertinent role or task; and records of Continued Professional Development (CPD) and/or Recognition of Prior Learning (RPL).

As new technology continues to emerge and develop, a portfolio of evidence will increasingly include emails, data sets, program/application outputs, e-based learning, e-workshops etc.

Utilising the experiences of the learning profession by adopting a competency model and framework has considerable advantages, as identified in this article. Such an approach has been successfully applied by the author in the fields of road safety and traffic engineering and can break any historical dependency on rank (‘next in line’) and/or time serving (‘length or service’). The latter has been identified as an issue in the industry, with too much expectation (or perceived right) that a person will be promoted to fill a senior role, enter a development pathway or gain permission to fulfil a specific task such as road safety auditing or leading post incident investigations, just because they have met a time-based criterion and/or been doing a similar job for a certain length of time. Such practice is only valid and not subject to question where a robust, objective assessment of competency also typically takes place.